In this post, I preview September’s PubSci, consider topics raised in August’s talk, and ask whether the Bard knew about Tycho Brahe as well as looking forward to International Microorganism Day.

September’s PubSci is booking on Eventbrite

September’s talk on Shakespeare’s Maths with Rob Eastaway is just a few days away and 70% of tickets been snapped up at the time of writing. I’ll say a bit more about it towards the end of this blog piece but head to the booking page now if you don’t want to miss out.

Is AI About To Conquer The World?

Since time immemorial, societies dreamt of non-human servants to carry out their chores.

Golems, Genies and shoemaking elves inhabit folklore but things nearly always go wrong as the creators lose control and the helpers go rogue. Remember Walt Disney’s Fantasia when Mickey Mouse learnt — as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice — how to make a broom carry water but didn’t learn how to stop it? Will it be the same story with AI? Are we just falling into an ancient fear?

Many of us have questions about AI and want to understand it better. On Wednesday 20th August Ruth Stalker-Firth came to the Old King’s Head to share insights from her three decades of involvement in AI. Perhaps the most significant point to come across in Ruth’s informative and entertaining talk was the number of times great claims have been made for AI in the past, only for them to fall embarrassingly flat, often leading to an “AI Winter” of reduced interest and research funding.

There have been two major AI Winters so far, one in the ’70s and one in the ’80s. In 1984 (of all years!), leading AI researchers Roger Schank and Marvin Minsky warned the business community that enthusiasm for AI had spiralled out of control in the 1980s and that disappointment would certainly follow.

One of the most famous cases of overstated claims for artificial intelligence was a chess playing automaton first displayed in 1770, known as the Mechanical Turk. This wonder of ingenuity and mechanics was constructed by Wolfgang von Kempelen to impress Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. The “Turk” not only played chess against human opponents to a high level, it could perform the knight’s tour, a puzzle that requires the player to move a knight to visit every square of a chessboard exactly once. It was so convincing that some onlookers believed the automaton to have supernatural powers, even that is was possessed by evil spirits — a ghost in the machine, if you like.

The fraudulent “Mechanical Turk” chess robot

This belief that objects which behave in human-like ways must have human-like reasoning arises from what philosophers call Theory of Mind. When I interact with you as another human, I have ‘theory of mind’ concerning you. I essentially project this onto your behaviour based on our interactions, and so I see you as conscious. It’s the basis for many superstitious beliefs and it also causes us to infer a personality in objects and systems that don’t actually possess them.

When Shakey, a 1966 wheeled robot dubbed “The first electronic person” was observed doing a twizzle at the end of its day exploring its environment, some observers thought it had evolved playfulness or even joy. The mundane reality was that it had been programmed to run with a tether but was now running without it. The twizzle dance that Shakey performed at the end of every day was programatically coded to ensure the (non existent) tether didn’t get progressively tangled, but to onlookers it looked like Shakey was playing and therefore conscious.

The fact that we anthropomorphise objects with surprising ease is something cartoonists and animators make use of all the time. Disney cartoons are famous for making a broom, a clock or a candlestick seem like human-like in their behaviour, and we willingly go along with it. Are we simply making the same mistake with the sophisticated outputs of ChatGPT and other Large Language Models? Have we conflated passing the Turing Test with actually possessing conscious agency, which is an entirely different matter?

The Mechanical Turk was a sophisticated device, with a complex set of levers and pulleys but it wasn’t an automaton and it couldn’t play chess. Hidden inside the base, behind fake gears and rotors, sat a human chess player. The device was incredibly ingenious, allowing the human inside to see the moves played on the board above and transferring his own moves back to the board through the mechanical arm. It was a work of engineering genius, but it wasn’t a robot and it wasn’t intelligent.

In a 1970 interview with Time Magazine, the founder of MIT’s AI lab Marvin Minsky, made the extraordinary claim that artificial general intelligence rivalling that of humans would arrive within the decade.

Marvin Minsky, 1970

“In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being. I mean a machine that will be able to read Shakespeare, grease a car, play office politics, tell a joke, have a fight. At that point the machine will begin to educate itself with fantastic speed. In few months it will be at genius level and a few months after that its powers will be incalculable.”

Clearly artificial general intelligence (AGI) still hasn’t arrived, but are we now, finally, on the brink of it? And should we be concerned this time? Well, just like von Kempelen’s chess playing illusion — and the Wizard of Oz for that matter — a lot of what we take for human-like AI is actually performed by humans, often poorly paid workers in developing countries. Is this the real ghost in the machine?

AI is pretty good, but Amazon Fresh doesn’t trust it to perfectly track your purchases. It employs 1000 people in India to manually check 70% of transactions. Amazon points out that human reviewers are common where high accuracy is demanded of AI. Open AI employed Kenyan workers on a tiny salary to make ChatGPT less toxic, and several AI-powered drive-thru fast food joints were using humans in the Philippines to act as AI.

Famously, AI-powered drive-throughs by Taco Bell and McDonald’s had to be pulled due to serious glitches such as putting bacon on ice cream, adding £222 dollars worth of nuggets and refusing to accept that a drink order was a drink order.

Whilst some analysts are warning that this time Generative AI will change everything (for better or for worse), others are cautioning it’s already as good as it will get and that the AI bubble is about to burst. Meanwhile, headlines are pouring in that 95% of companies have seen no return on their Generative AI investment, or that another AI winter is coming. So where does that leave us ordinary users?

Aside from the well-known, and poorly managed, risks of biased training data leading to biases in AI — a reflection, of course of the human world — we simply need to beware of mistaking AI for a little elf that does our bidding.

AI is limited. Its data is finite. Its understanding is zero. Here, ChatGPT shows that it never understood the famous “I can’t operate, it’s my daughter” lateral thinking puzzle. It doesn’t just have biases, it has weird ones.

AI is a tool that can be useful but is limited. It isn’t sentient, but it also only has the morals and safeguards we build into it. Mickey Mouse’s enchanted water-carrying broom is really the model for a famous AI thought experiment called the Paperclip Maximiser which highlights the danger of giving carelessly formed instructions to a powerful but unthinking AI-controlled system.

Agentic AI is the new trend of letting AI do things for you rather than simply asking it a question. It can book flights for you but it will need access to your credit card details for example.

In the words of Donnchadh Casey, CEO of CalypsoAI, a US-based AI security company, “If not given the right guidance, agentic AI will achieve a goal in whatever way it can. That creates a lot of risk.” If agentic AI is the Paperclip Maximiser made real, we must establish rules and standards for how it behaves and how it is limited because, unlike the sorcerer’s apprentice, there is nobody to step in if it goes rogue.

September PubSci is nearly upon us – BOOK NOW!

That was a longer digression into AI than I planned so lets’s focus on this month’s PubSci.

On Wednesday 17th September, PubSci is delighted to welcome author and broadcaster Rob Eastaway as he draws back the stage curtain to reveal the extraordinary mathematics of William Shakespeare’s day and its role in his plays in Much Ado About Numbers? – Shakespearean Maths.

Rob uses humour and insight to explore why the Tudors multiplied so quickly, and how dice-rolling was a hazard as we discover the surprisingly funny ways in which Shakespeare used numbers in his writing.

Rob Eastaway is the award-winning author of ‘Why do Buses come in Threes?’ and will be signing copies of his latest book, Much Ado About Numbers, after the talk. To be there or not to be there..? That’s not even a question!

You can read all about it on the current Next Event page or go straight to booking on Eventbrite. Remember, only a handful of tickets are left, so don’t delay.

~

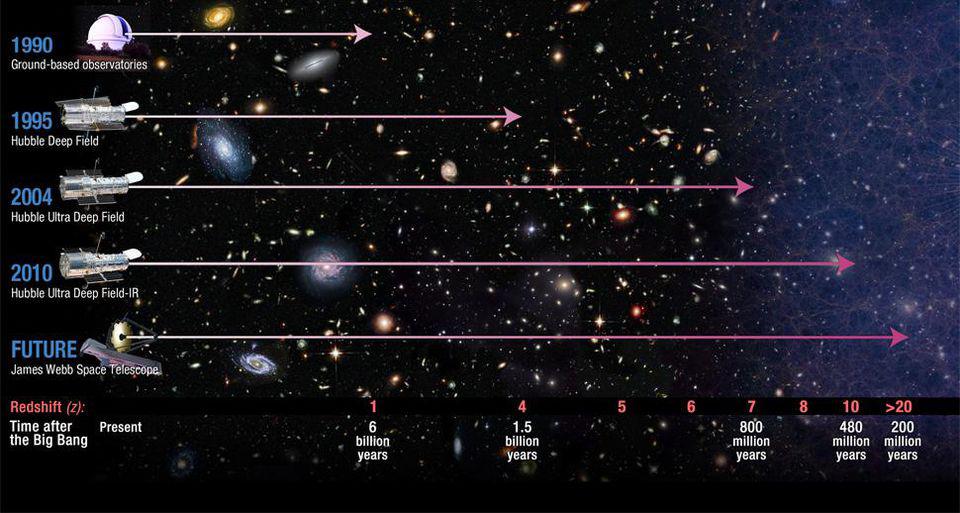

Methinks I have astronomy

Talking of Shakespeare, it seems he wasn’t only interested in the maths of his day. He may also have kept somewhat up to date with the science of his day, especially astronomy. Here’s a line from Sonnet 14 in which it seems he’s distinguishing astronomy from astrology:

Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck; And yet methinks I have astronomy, But not to tell of good or evil luck.

A friend recently sent me a delightful podcast from Scientific American in 2014 in which Author Steve Mirsky discusses the possibility that Shakespeare knew about the eccentric (but hugely important) Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and referenced him in Hamlet. I won’t duplicate it here — this blog is already longer and later than I intended — I’ll just say that if a drunken Elk, a golden nose, a private observatory-castle on its own island, and a bizarre death don’t grip you (in a sort of comedy Bond villain kind of way), at least read up on Brahe for his huge contribution to astronomy such as highly accurate observations in the pre-telescope era. You can read a transcript of the podcast here.

“Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar; But never doubt I love.” Hamlet Act 2 Scene 2

~

International Microorganism Day

On 17 September 1683, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek – a Dutch merchant with no fortune or university degree – sent a letter to the Royal Society of London with the first description of a single-celled organism after he made the first simple microscope. He originally wanted to check the quality of cloth in his drapers shop, and small folding magnifiers are still known as “linen checkers” to this day, even when used for entirely different purposes. After being given a basic microscope for a birthday while at primary school, Van Leeuwenhoek became one of my childhood heroes.

Whilst I didn’t follow him into a career in microscopy (as I thought I would at the age of 9), I’m very happy that 17th September is now recognised as International Microorganism Day.

Obviously you’ll be at PubSci in the evening, but if you have time during the day, why not brew beer, ferment kimchi, watch tardigrade videos, admire Petri dish art, or simply raise a toast to the invisible life forms keeping our planet running!

Indeed, where better to raise a glass of something microbiologically-made than the upstairs room of the Old King’s Head at Much Ado About Numbers? – Shakespearean Maths!

In a curious scheduling coincidence, October’s PubSci is on problematic microorganisms, as Prof Jenny Rohn talks about the never-ending battle against Antimicrobial Resistance on Wednesday 15th October. Don’t forget you can keep up with forthcoming events by subscribing to our Google calendar or downloading the programme (see below). You can also follow us on Eventbrite to be notified when tickets become available for new events.

Lastly, apologies for sending this blog out so late. I do all this in my free time, and my free time has lately been taken up with other projects, not least of which involves some rather exciting news. I’ll be presenting a science radio show on Resonance FM, London’s Arts Council-funded community radio station, and I’m delighted to say that Mike Lucibella will co-present. We’ve recorded the first monthly episode and are editing it before a broadcast date is announced. Despite the name, you can listen to Resonance on DAB, streaming and Soundcloud (for playback) as well as good-old FM radio.

I’ll be posting news of the broadcast dates and links to our Soundcloud as soon as they’re available.

Thanks for reading. Please feel free to email or comment in response. Hope to see you at The Old King’s Head on Wednesday 17th September.

14/9/2025 Posted by Richard, PubSci programmer and host

PubSci: Sipping • Supping • Science

• • •

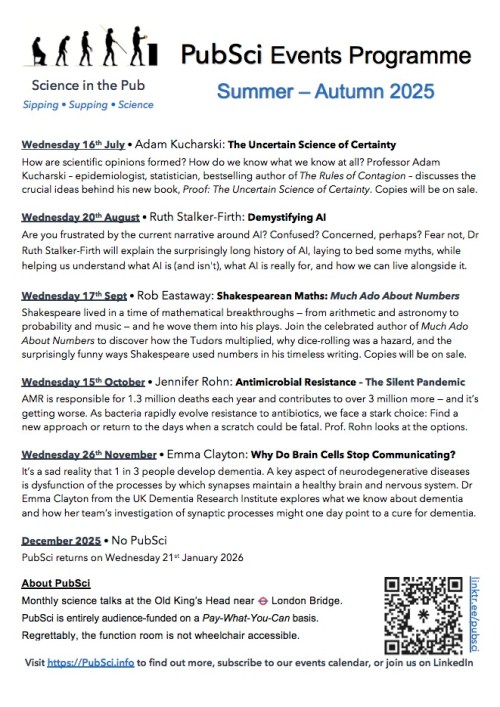

The Summer / Autumn Programme

PubSci’s latest programme runs from July to November (there’s no event in December) and is perfect for printing out and pinning to your work noticeboard or sticking to the fridge, It’s always available on the Current Programme page, along with past event programmes, and you can link to the image below on your own website.

• • •

Keeping Up With Future Events

To make sure you don’t miss out on future events, subscribe to our Google Calendar to be the first to know when new talks are scheduled, and follow PubSci’s events on Eventbrite to be notified when tickets are available. You can also sign up to our own mailing list on any page on this site.

• • •

About PubSci talks

PubSci is organised and hosted by science communicator, Richard Marshall, assisted by Mike Lucibella. Events are held upstairs at the Old King’s Head, near London Bridge tube. No specialist knowledge is required, just curiosity. Doors open at 6.30pm for a 7pm start. Talks run for ~45 minutes and are followed by a Q&A session. The Old King’s Head has a happy hour before 7pm, and the kitchen serves excellent pub grub.

There is no charge for attending PubSci talks, but we have a cash whip-round to cover expenses on the night – consider it “Pay What You Can Afford”. As few of us carry cash these days, you can make a donation when registering for ticketed events with Eventbrite. Please help us continue putting on events. PubSci has no other source of funding.

We aim to keep PubSci accessible for all, although it is unsuitable for under 18s as we meet in the function room of a pub. Regrettably, there is no wheelchair access.

You can find all our links on our LinkTree.

Address:

The Old King’s Head (upstairs room)

King’s Head Yard

45-49 Borough High Street

London SE1 1NA